Yesterday, I heard Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach being interviewed on NPR’s Talk of the Nation, discussing new voter registration laws requiring photo IDs as a means of preventing voter fraud. The debate is an emotional one, but Secretary Kobach put things in a highly quantifiable way:

“Colorado found 11,000 aliens on their voter rolls, of whom nearly 5,000 voted in the 2010 election. So that’s 5,000 U.S. citizens whose votes were canceled out.”

Rather than addressing the volatile issues surrounding immigration and voting rights, he changed the conversation in a highly quantifiable way:

“5,000 U.S. citizens whose votes were canceled out.”

Using statistics, Kobach transferred the emotional weight from concern about discrimination to the legal voters “robbed” of their democratic rights.

This demonstrates that statistics and data can be marshaled by the well-prepared and the well-spoken to contribute to the emotional side of any issue or marketing effort.

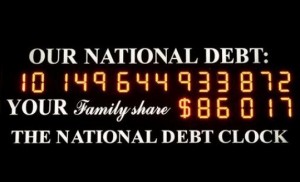

Another example: The national debt clock in Times Square that keeps a running—and increasing—total of the national debt is a highly visual, yet data-intensive, method for getting folks to feel some urgency regarding the national debt.

The Doomsday Clock is a similar device. Maintained since 1947—the beginning of the Cold War—by the board of directors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists at the University of Chicago, it is a symbolic clock face which visually and quantifiably estimates the level of risk of nuclear war based on world events in terms of minutes before midnight. Over the years, it has ranged form 11:48pm to 11:57pm.

The more that communicators can leverage data to create such persuasive arguments, the more successful they can be at appealing to both heart and head of each member of their audience. The remarkable thing to consider is just how emotional data can be, and also how effective it is at changing minds and behavior.

Consider these two statements:

1. We should all turn our computers off at the end of the workday to save energy.

2. If everyone in America turned off their computers at the end of the workday, it would save $2.8 billion and 20 tons of CO2 per year—enough to power the Empire State Building inside and out for 30 years.

Both statements are true, but only one makes you seriously think about shutting off your computer before you leave your office today.

Most marketers understand that a heart full of emotion usually trumps a head full of facts. But facts—data—can be made to serve the emotional side of any marketing message.